Interview: Seniha Ünay / About

Translation: Burçin Nilay Kalınbayrak / About

The guest of the October issue of Narratives Interview Series is the artist and lecturer Gülçin Aksoy. We talked about her works from different periods through her subjects, materials, and production process. At the same time, we had the opportunity to hear her teaching perspective in the frame of the Tapestry Studio, her collective work practices, and her approach to the masculine language.

“Sometimes I am like a shadow wandering in memory and its side effects.”

You are a lecturer at “The Tapestry Studio” of Mimar Sinan Fine Arts University (MSGSÜ) Painting Department, a studio open to production, sharing, and collective thought. We remember that you said “For me, teaching is to contribute” Could you mention the aspect of “contributing” and the spirit of “The Tapestry Studio”?

The day before, I was telling one of our research assistants about my effort to find my way and to be integrated with art without drowning under the drudgery of the years when I was a research assistant. I said, “After a while, I think that I set things right by engaging in art, making my job a part of myself, and therefore not separating teaching and being an artist from each other.”

Of course, this method did not come from the sky. Not separating teaching and being an artist from each other was something spontaneous or something forcing the spontaneous, but still, something achieved through effort. Looking from this frame that enriches my life, being a teacher reached the condition of “learning together” from its usual “teacher” form (mastership didn’t even get close to me), and being with my students became indispensable in my life.

My adventure, which started at the Engraving Studio of MSGSÜ Painting Department, has been continuing at the Tapestry Studio. Shaped through the classical tapestry tradition, the Tapestry Studio was established in 1976 by my dear teacher Zekai Ormancı, a faculty member before me. Today it is a studio facing towards contemporary art according to my interest and my field, I guess. It contains the tradition in itself, loves and prepares its looms, makes individual or collective weavings and performances or takes in any kind of necessary medium. What I am mentioning as if it was a legal entity (let’s get attached to bureaucracy) is this spirit of the Tapestry Studio constituted with the contribution of whom enters or exits the studio over the years. It is an open studio, the door is never locked. It is a completely public space. However, in these areas, public space belongs to the state while the public already belongs to the state. Still, I try to open the studio to everyone apart from all those specific student or teacher identities. It remained open, it is still open. Therefore, it has become a space where the known hierarchy does not stop by, everyone has a place and this idea is adopted. We have sat, worked, and produced altogether in the studio. Whoever needs what, we have shaped the Studio accordingly. We and I have contributed. I think contributing means making way.

The Tapestry Studio at MSGSÜ

There is a collective thought and production processes in your works like “More on the Agenda” with the Atılkunst team, or the exhibition “Our Leaving Will Be Magnificent” organized in the apartment building named Peace where you lived together with other artists, and the works at “The Tapestry Studio.” From this perspective, could you talk about how you define collective thought and its advantages and disadvantages?

In fact, rather than collective thought, it would be better to talk about individual thought, and experience and skill of working together that goes along with it. I guess it is also related a little bit to the times and places that I grew up. I was in a comfortable and uncomplicated environment without significant class discrimination. Until the September 12. I think I catch and transform the world with an eye-level glance in my own way. I think the word collective has been filled with the neglect of individual existences, and the practical equivalent of the word ended up with centralized, monotheistic communities where individuals were ignored. There were plenty of examples in the jargon of the Left of the past. Not to even mention the other wing. It even happened like this in the field of art. Although I have a lot of experience in collective art works, most of those who are referred to as collective could not go beyond serving the needs of some big brothers. At this point, I should specify that I find it very important for a person to reach individual awareness by putting effort on himself/herself. Working with an advanced individuality is much better than working with an insecure, obedient version of the self which is not endeavoured. Individual production is important, besides, it will be even more beautiful if it is shared and cooperated. I’m not talking about vertical additions like adding storeys, but horizontal gatherings. The togetherness I mention or care about does not correspond to the collective concept that is shaped around and expanded in line with the goals of the mustached big brothers of the past. I am talking about the partnerships where individual needs are valued and even the sharings are shaped on these needs and the cooperations that are shaped by individual needs while working together. Of course, the gatherings where everyone’s needs are important, not the big brother’s…

“I prefer the unfinished, the ongoing rather than showing off like ‘I display and share my finished, magnificent artwork.'”

Atılkunst was born out of necessity, then ended when the needs of individuals disappeared. There is no rule that togetherness will last a lifetime. The important thing is to keep the goodwill alive and the mind open.

The non-hierarchical exhibition “Our Leaving Will Be Magnificent”, as well, was born out of necessity in our dear building (we call it the Peace Apartment Building.) We are together with artists, sometimes students, and my dear assistants who are all artists. Due to the vacation of the building, we thought we would say goodbye to our building with an exhibition called “Our Leaving Will Be Magnificent.” Oddly enough, we still haven’t been able to go.

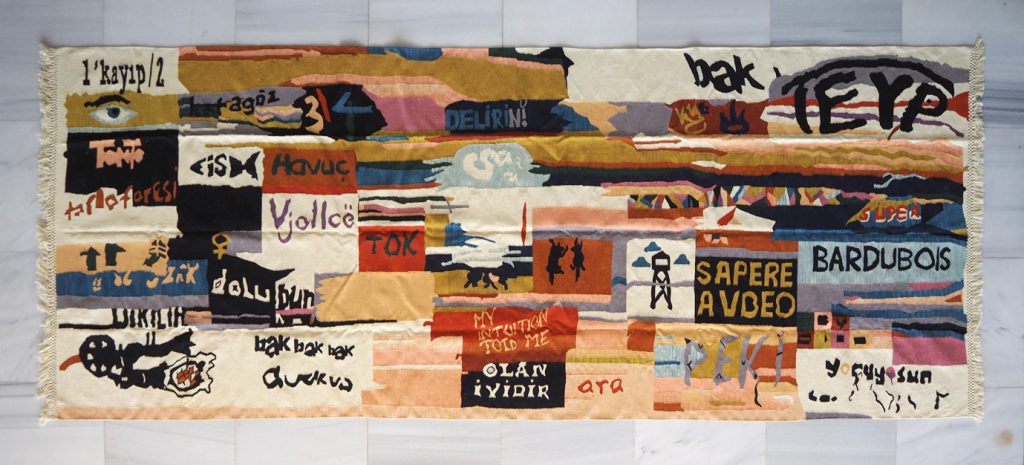

Being together is difficult, yet pleasant as well. It takes effort to keep the doors open constantly and to ensure dialogue between people. The Tapestry Studio is a place where togetherness and needs are shared. The practice of mutual listening and producing developed while expressing and caring for individualities has become the tradition of the studio. The master-apprentice relationship is thrown out, but the previous one carries this practice to the next one in his/her own way. A good example for all that I told is the “Graffiti Tapestry” in which all the students or friends who worked in the studio were personally involved. All-comers write the sentence or word they want by weaving.

I personally do not like being alone all the time. I feel like if I have to stay with myself, then I have to carry that self somewhere or have to share it. I prefer the unfinished, the ongoing rather than showing off like “I display and share my finished, magnificent artwork.”

“Graffiti Tapestry”, Academiae Biennial, İstanbul, 2018.

You sometimes tell well-known stories in your works such as “Double Story” and “Independence Path” or you sometimes transform ordinary objects and spaces that we are all familiar with like in your works “The Family Cemetery I Love” and “Chorus.” Could you tell us how you determine and shape the relationship you establish with space, people, and objects in your production process?

Let’s say they are the ordinary versions of ordinary stories read backward or beyond the dialectical method, these are the stories that expand in the gaps and have trouble with beginnings and endings. At least mine are like that… These are the stories of all of us anyway.

Every story, of course, starts with myself. The places and objects that touch and shape me… “Double Story” was really my story. In other words, I was setting out with what happened and fictionalizing randomly. My road was about what happened to me, and to many others accordingly on the way. It started with “Untitled to Death” with its tiny signboard next to it dated 1980. There were places where childhood passed, places that transformed, and disappeared. Childhood memories are often stuck in mind with places. Going to the places where my childhood passed, following the transforming face of the space made it possible to produce the space and draw a road map of a transforming mind. The journey that reaches here and the strange reading that follows it did not cause to tell a history but to wander through the gaps of individual history, thanks to the art starting with the lowercase “a”, the material on hand. In “Double Story” I said “loneliness and fatigue between 1 time and 1 space”.

“The Family Cemetery I Love” came into leaf in a small, high-ceiling space that had nothing to do with my past but with me. I say it came into the leaf because it really did at the end. I had come across a space. I had worked inside that space for two years, filling the interior of the space. The quite minimal arrangement that emerged as a result was, I think, a merging point of the outside (Thursday Market), the inside (hardware store), and the past (losses), specific to the space. At least for that moment. A space that still exists between presence and absence, that is produced. Heartfelt thanks to dear Korhan Erel’s sound installation… Then the space was produced, of course socially.

“Independence Path” is a striking “moment” of the story of my return to the hometown I left many years ago. When I saw the sculptures of Atatürk and his 18 fellow soldiers settled on the coastline, coming towards me from the sea, my first reaction was that “I think I will work here for a while.” With pain and pleasure, of course. Broken, fake, but real. Still cute. Like temporary faces of perpetual ideology.

Spaces determine thoughts, thoughts determine spaces. Every government wants or does not want to build spaces, but builds to be permanent, to live long. Just as there are powers that founder in the temporality of wood, there are demolishers in concrete buildings who destroy them instantly even though they are made of stone. As if we are living the days of “Who will destroy more quickly?”

Sometimes I am like a shadow wandering in memory and its side effects.

When it comes to people, there are some in my mind, and some I can touch. The ones I care about are not those who become concrete, petrified, but the ones who are not heroes; not the big brothers in the “Chorus of Conductors”, but the ones who wrote the real story in between. The relations that weave those carpets, that make them to be weaved, people like Ahmet Aksakal who are a part of the whole. It’s like starting the story in the middle. Dealing with the ones that establish the connection between heroes.

Gülçin Aksoy, “The Family Cemetary I Love’, Side Specific Installation, 2018.

“We were thought to be men as a result of the daily relations of the vertical consciousness.”

Ahu Antmen titled her article on you as “Gülçin Aksoy: Weaving and Touching.” What are you touching and weaving? Could you touch on the language of the material in your art?

How nice of you to remind me of the beautiful article of dear Ahu and the place where she caught me. One of the exhibitions we held in the beginning of this summer was called “To Touch Despite Everything”, a tapestry exhibition in the first place. It has been eight years since Ahu’s article. I am still weaving, touching. Priority is the self-touch and then perhaps to hint at power mechanisms, masculine discourses (including triangle composition.)

The range of my art production is wide. I come from the tradition of painting, draw, and write if necessary. Sometimes I write by weaving.

As you cannot escape the determinative character of the material, it is necessary to read and transform the material as well. I have materials determined according to my opinion. Your medium can be your idea (Medium is the message), so is the weaving act.

Weaving has a simple logic. Briefly, it consists of plus and minus or even 0 and 1 in today’s digital language. By being out of this relationship, you can get lost in the chain of possibilities despite the simplicity of thought and action. This goes all the way to the infinite variety of weaving and the endless integrity of relationships reaching today’s computer technology.

A slight shift in this relationship causes weaving. It is functional and useful, and vital because of its usefulness.

On the other hand, it is a well-known proposition that weaving, the act of touching is physically identified with the woman’s touch. As for me, the fact that the masculine is not inspired by such a vital action causes a feeling of “pity” for centuries. What a loss…

Weaving is also an action that keeps people in the now because of constant repetition and slowness sometimes. The course of thought in accordance with the slowness and movement of the hand… Yes, an action that keeps people in the now.

In these times that we are longing to touch, we confine ourselves with mental satisfaction in front of the screen. That does not work, remains incomplete.

Gülçin Aksoy, “Chorus“, Galata Rum School, Istanbul, 5-30.09.2018.

We want to ask an open-ended question: “Why were we thought to be men?”

The exhibition “A” was about reading the masculine language and codes through the language. It was dealing with the issues such as growing up in the “baba (father)” culture starting with B despite the word “anne (mother)” starting with A, the first, the primary letter of the alphabet or having a language like Turkish which does not divide words into genders but has the words “abi (big brother)” and “abla (big sister)” that other languages don’t have. After all, we had handed our genderless language over to paternal terminology.

What I’m talking about are the means of the masculine language, the share of the language in the construction of masculine culture. In order to reach a horizontal, eye level, it is necessary to dig down deep in any case. When it comes to the letter A in ordinary language, as an answer to the question “Why were we thought to be men?”, I say “We were thought to be men as a result of the daily relations of the vertical consciousness.” We used to send emails to people every weekend without asking them. Sometimes we geeked out and get into action. Then we were connecting with Mr. Atıl from beyond. In fact, Mr. Atıl was not there, but everyone thought he existed. On the other hand, “Kunst” was connected from foreign geography. Of course, we were thought to be men.

However, the first sin was not the apple, but the writing… It was Adam, not Eve. It was what we wrote.

Gülçin Aksoy, “A“, Zilberman Gallery, İstanbul, 11.11-30.12.2017.

* Starting point of the question “Why were we thought to be men?” was the story of the Atılkunst team that was active between 2006 and 2013 and consisted of women but were thought to be men as they did not reveal their identity.

Our thanks are due to Gülçin Aksoy.

- For more information about the artist, you may visit her website.

- All the photos in this interview are sent by the artist or taken from her website, and used by the courtesy of the artist.

- The rights of all the visual and textual concepts in this interview are reserved. Quotation shall be allowed provided that the source shall be mentioned in the work where the quotation is cited. For the photos please contact the artist.

Please click for more information about Narratives Interview Series.